Diaphragmatic hernia: causes, symptoms, treatment

Diaphragmatic hernia: Description

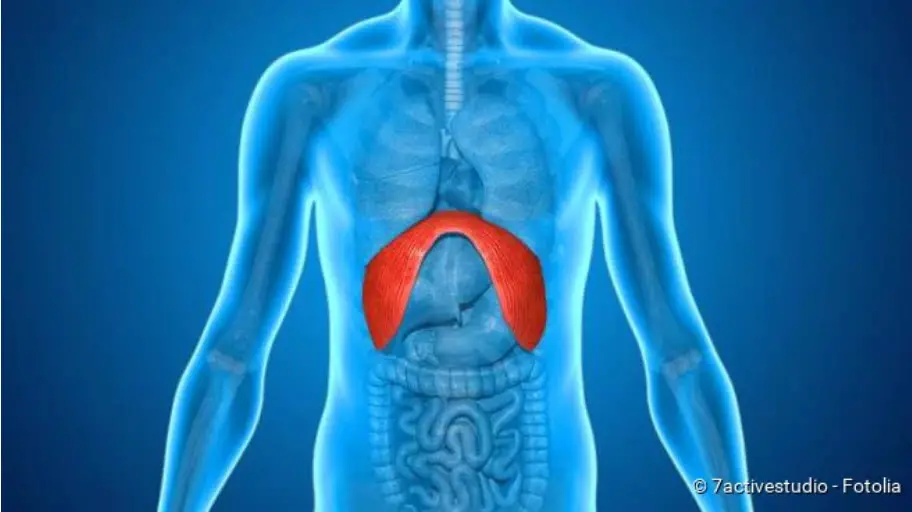

In a diaphragmatic hernia, medically called hiatus hernia, parts of the abdominal organs are displaced through an opening in the diaphragm (diaphragm) into the chest (thorax). The dome-shaped diaphragm consists of muscle and tendon tissue. It separates the chest from the abdominal cavity. It is also considered the most important respiratory muscle. It has three large openings: In front of the spinal column is the so-called aortic slit, through which the main artery (aorta) and a large lymph vessel pass. The aorta runs behind the abdominal cavity and its organs. The inferior vena cava runs through the second larger opening – it is firmly fused with the surrounding tendon tissue of the diaphragm.

The oesophagus passes through the third large hole, the hiatus oesophageus, where it enters the stomach just below the diaphragm. The opening of the oesophagus forms a direct connection between the chest and the abdominal cavity. Since the muscle tissue is relatively loose at this point, a diaphragmatic hernia can occur especially here.

Hiatus hernias are subdivided according to the origin and location of the parts that enter the thoracic cavity.

| Type I Hernia | = axial hiatus hernia

The stomach entrance (cardia), where the esophagus merges with the stomach, moves vertically upwards (more precisely along the longitudinal axis of the esophagus) through the opening. It then lies over the diaphragm. This diaphragmatic hernia often also affects the entire upper part of the stomach, the gastric fundus. |

| Type II hernia | = paraesophageal hiatal hernia

A varying proportion of the stomach passes next to the esophagus into the chest. However, the stomach entrance remains – and in contrast to type I hernia – below the diaphragm. |

| Type III Hernia | This diaphragmatic hernia is a mixed form of type I and II. It usually begins with an axial hiatus hernia. Over time, more and more stomach sections are moving into the chest area, also to the side of the esophagus. The extreme form of this hiatus hernia is the so-called “upside-down stomach”: The stomach lies completely in the chest. |

| Type IV hernia | This is a very large diaphragmatic hernia in which other abdominal organs such as the spleen or colon also enter the chest cavity. |

The commonly used term diaphragmatic hernia usually means the displacement of an organ through the esophageal slit (Hiatus oesophageus), therefore also called hiatal hernia. In addition, there are also diaphragmatic hernias in which organs of the abdominal cavity pass through other openings of the diaphragm. These are summarized under the term extrahiatal (i.e. outside the esophageal slit) diaphragmatic hernias. For example, there is a hole (Morgagni) at the junction with the sternum, through which intestinal loops are preferably displaced (Morgagni hernia, parasternal hernia). And a triangular gap in the back of the muscular diaphragm (Bochdalek gap) can also cause a hernia.

Frequency

The diaphragmatic hernia through the esophageal slit is by far the most common form. Among these, axial hernias are found in about 90 percent of cases. Fractures lateral to the esophagus, the paraesophageal hernias, on the other hand, occur very rarely alone. They are usually found in mixed forms (type III hernias). Diaphragmatic hernias are more common in older people. If the hernia is caused by a maldeveloped diaphragm, it is the congenital form. Doctors find a diaphragmatic defect in about two to five out of 10,000 births. Most of them are on the left side (80-90 percent).

Diaphragmatic hernia: Symptoms

Whether one has symptoms with a diaphragmatic hernia usually depends on the type and extent of the respective hernia.

Axial hiatal hernia

Type I diaphragmatic hernia usually does not present any symptoms. Patients often report heartburn and pain behind the sternum or in the upper abdomen. However, it is less a matter of diaphragmatic hernia symptoms; rather, the symptoms are due to an accompanying reflux disease. This causes stomach contents, especially the acid gastric juice, to flow into the esophagus. Normally, a closing mechanism prevents this reflux: muscle pulls at the stomach entrance (lower esophageal sphincter) tense up and thus protect the esophagus from gastric acid. In addition, the esophagus opens very steeply into the stomach. This circumstance makes reflux even more difficult.

However, the healthy diaphragm supports this process, which is why the risk of reflux increases in case of a rupture. Possibly the upper end of the diaphragmatic hernia narrows and a so-called treasure-ki ring is formed. As a result, patients suffer from swallowing disorders or steakhouse syndrome: a piece of meat gets stuck and clogs the oesophagus.

In individual cases, cramp-like pain in the upper abdomen occurs as symptoms of diaphragmatic hernia. These occur when the hernia sac is pinched. If the diaphragm opening presses too hard on the leaking stomach section, damage to the stomach wall may occur. Doctors refer to this as the Cameron ulcer.

Paraesophageal hiatus hernia

At the beginning of a type II diaphragmatic hernia there are usually no symptoms. As the disease progresses, patients find it difficult to swallow. In some people affected, stomach contents flow back the oesophagus. Especially after eating, patients often feel increased pressure in the heart area and circulatory problems. If the hernial sac twists, its blood supply is also disturbed and the sections of the stomach contained in it can die off. Doctors speak of this event as an incarceration, which is life-threatening.

As in axial diaphragmatic hernia, the tissue of the stomach wall can be damaged. Under certain circumstances the resulting defects bleed unnoticed. Approximately one third of all type II hernias are therefore only discovered through chronic anaemia. The remaining two thirds find doctors by chance or show up with swallowing difficulties. If a hiatal hernia causes severe symptoms, the hernia sac is usually very large. In extreme cases, the entire stomach shifts to the chest.

Further diaphragmatic hernia

The symptoms of extrahiatal diaphragmatic hernias are similar. Some patients have no symptoms at all, in others these diaphragmatic hernias are more complicated. For as with hiatus hernias, the contents of the hernial sac – intestinal loops or other abdominal organs – can die and release toxins that are life-threatening for the body.

Special care should be taken with newborns. A diaphragmatic hernia is almost always life-threatening for them. This is because the transferred parts of the abdominal cavity displace the heart and lungs in the still small chest.

Diaphragmatic hernia: causes and risk factors

In the case of a diaphragmatic hernia, a distinction is made between congenital and acquired forms. The latter has various causes and dimensions. Congenital diaphragmatic hernias, on the other hand, are usually the result of a maldevelopment of the diaphragm.

Developmental disorders during the embryonic period

The diaphragm develops in two phases. First, a wall of simple connective tissue separates the thoracic and abdominal cavities. Since the diaphragm is made up of two parts (septum transversum and pleuroperitoneal membrane), there is initially a gap. This closes faster on the right than on the left. In the second phase, the muscle fibres grow in. If a disorder occurs during this period (fourth to twelfth week of pregnancy), a defect in the diaphragm develops. Through these gaps, parts of the abdomen can now shift into the chest. Since organ sheaths such as the peritoneum are not yet developed at the beginning, the organs lie freely in the thoracic cavity.

About seventy to eighty percent of all paraesophageal hiatal hernias are due to a congenital diaphragmatic defect. Often in developmental diaphragm disorders there is a large opening through which the esophagus and the aorta run together (hiatus communis).

Risk factor body position

The axial diaphragmatic hernia is also called sliding hernia. The ruptured abdominal contents can slip back and re-enter the chest area. So it slides back and forth between the chest and abdomen. The stomach sections shift mainly when lying down or when the upper body is lower than the lower abdomen. If the affected person stands upright, the displaced parts of the force of gravity return to the abdomen.

Pressing as a risk factor

The probability of a diaphragmatic hernia is increased when the abdominal muscles are tensed. This “pressing” increases the pressure in the abdomen. As a result, the stomach, which lies directly under the diaphragm, is pushed upwards through the weak or defective diaphragm. The risk increases even with forced rapid exhalation, abdominal pressure and defecation.

Risk factor obesity and pregnancy

Similar to pressing, obesity (obesity) and pregnancy also increase the risk of diaphragmatic hernia. An excessive amount of fatty tissue in the abdomen (peritoneal fat) increases the pressure on the organs, especially when lying down. This displaces them – especially upwards. During pregnancy, the child growing in the uterus increasingly requires space in the abdominal cavity. The organs are pushed upwards. Usually such a diaphragmatic hernia regresses without problems after birth.

Risk factor age

Already in a study from 1990, a connection between age and the occurrence of a diaphragmatic hernia was investigated. In people who are older than 70 years, diaphragmatic hernias can be detected in 70 percent of cases by X-ray. Experts believe that the connective tissue of the diaphragm becomes weaker and the esophageal slit widens (becomes worn out). In addition, the ligaments between the stomach and diaphragm loosen where the oesophagus merges with the stomach. The oesophagus thus opens into the stomach more shallowly than normal. Doctors speak of a cardiofundal malposition or an open esophageal-stomach transition, which increases the risk of diaphragmatic hernia.

Diaphragmatic hernia: diagnosis and examination

Many hiatus hernias are discovered by chance when the doctor performs an X-ray or a control gastroscopy. Usually this is done by a specialist in gastroenterology in the field of internal medicine, sometimes also a lung specialist (pulmonologist). Some patients suffer from heartburn with diaphragmatic hernia and should consult their family doctor with such complaints.

Medical history (anamnesis) and physical examination

When a patient with diaphragmatic hernia symptoms visits a doctor, he or she asks him or her specifically about the symptoms that occur: how exactly the symptoms manifest themselves, since when and in which situations they occur and what possibly aggravates them. In this context, already known, earlier diaphragmatic hernias of the patient are particularly important.

Since traumatic events such as an operation or an accident can also damage the diaphragm, such information plays a decisive role. In about 30 percent of patients, in addition to diaphragmatic hernia, a gallstone disease (cholelithiasis) and protrusions of the intestinal wall (diverticulosis) can also be found. Medically, these three common diseases are called Saint-Trias. The doctor will therefore also go into the previous medical history. If intestinal loops are displaced in the diaphragmatic hernia, the doctor may be able to hear intestinal noises above the chest with the stethoscope.

Further investigations

For the exact classification and planning of a diaphragmatic hernia treatment the physician carries out further examinations.

| Method | Declaration |

| X-ray | In an x-ray of the chest, an air bubble behind the heart and above the diaphragm can often be seen in a diaphragmatic hernia. This finding points mainly to hiatus hernia type II and III. |

| Breischluck, contrast medium | During this examination, the patient swallows a contrast medium slurry. Afterwards an X-ray is performed. The pulp, which is largely impermeable to X-rays, is clearly visible and shows possible constrictions that it cannot pass. Or it presents itself above the diaphragm in the chest in the area of the diaphragmatic hernia. |

| Gastroscopy

(Oesophagogastro-duodenoscopy, ÖGD) |

Sometimes a diaphragmatic hernia is discovered by chance when the oesophagus, stomach and duodenum are mirrored. The axial hiatal hernia is then manifested by a constriction below the actual gastric entrance or the lower esophageal sphincter. This method can also be used to diagnose a distinct constriction, the treasure-ki ring. A paraesophageal diaphragmatic hernia is difficult to distinguish from the mixed form. However, it is important to rule out or detect concomitant oesophagitis caused by gastric juice (reflux esophagitis), inflammation of the stomach (gastritis) or tissue damage (ulcer). |

| Esophageal pressure measurement | The so-called esophageal manometry determines the pressure in the esophagus and thus provides indications of possible movement disorders that can be caused by a diaphragmatic hernia. |

| Magnetic resonance tomography (MRT) and computer tomography (CT) | These more detailed imaging examinations are particularly useful for diaphragmatic hernias that do not pass through the esophageal slit. The detailed layer representation also plays a major role in planning the treatment, in this case an operation. |

| Ultrasound (of the fetus) | In the case of a congenital diaphragmatic defect, a fine ultrasound scan of the unborn child shows relatively early on whether an intervention is necessary. The doctor measures the ratio between lung area and head circumference and can thus estimate the extent of the diaphragmatic hernia. |

Diaphragmatic hernia: treatment

A diaphragmatic hernia does not always need to be treated. The axial hiatus hernia is only operated on if symptoms such as chronic reflux disease occur. Due to the backflow of gastric juice, the oesophagus becomes inflamed and the mucous membrane is attacked. Damage to the mucous membranes and bleeding may follow. If the reflux disease exists over a longer period of time, the risk of esophageal cancer is also significantly increased. If the mucous membrane has been damaged by a diaphragmatic hernia, a surgical intervention should also be considered.

In order to avoid possible discomfort caused by backflowing gastric acid, appropriate medication is also prescribed. They either reduce the amount of acid (proton pump inhibitors, histamine receptor blockers) or balance the acidity (antacids).

Hiatal hernia surgery

All other hiatus hernias are treated surgically. Even though symptoms of a diaphragmatic hernia can appear late, the hernia sacs often become larger and larger as the disease progresses. In case of complications such as a disturbed food transport, a twisted stomach or a trapped fracture content, which as a result can die off quickly, the doctors operate as soon as possible. In the process, the diaphragmatic hernia that has passed through into the thoracic cavity is properly repositioned back into the abdominal cavity. The hernia gap is then narrowed and stabilized (hiatoplasty). In addition, the gastric fundus, i.e. the dome-shaped upper bulge of the stomach, is sutured to the left underside of the diaphragm. At the end of diaphragmatic hernia surgery, the surgeons attach a part of the stomach either to the front abdominal wall or to another part of the diaphragm (gastropexy).

If the diaphragmatic hernia operation is only intended to remedy the reflux disease, the so-called fundoplication is performed. The surgeon wraps the stomach fundus around the oesophagus and sutures the resulting cuff. This increases the pressure on the lower esophageal sphincter at the mouth of the stomach and gastric juice can hardly flow upwards.

Plastic nets

If the diaphragmatic defect is too large, plastic nets are usually used to close the hernia gap. Caution is required, especially in the case of congenital defects of the diaphragm. The newborns have to be treated with intensive care, because the diaphragmatic hernia hardly allows for sufficient respiration. Artificial respiration is then necessary. Only when circulation and respiration are stable can surgery be performed.

Diaphragmatic hernia: course of disease and prognosis

In about 80 to 90 percent of the gliding hernia no therapy is necessary. And even after surgery, about 90 percent of patients with diaphragmatic hernia are free of symptoms. In newborns, the prognosis mainly depends on how much the lung volume is restricted. Since the diaphragmatic hernia is already present before birth, the lung on the affected side is usually underdeveloped. In severe cases the mortality rate is about 40 to 50 percent.

Complications

A diaphragmatic hernia is less likely to develop if complications arise. If the stomach or the contents of the hernia sac are twisted, for example, their blood supply is cut off. Consequently, the tissue becomes inflamed and dies. Toxins released in this way can be distributed in the body and cause severe damage to it (sepsis).

If large parts of the abdominal organs are displaced by the diaphragmatic hernia, the lungs and heart are constricted in the chest. This leads to circulatory problems and shortness of breath. In these cases, surgery is performed quickly and the patient is cared for in an intensive care unit. In addition, bleeding from tissue damage causes chronic anaemia.

lifestyle change

Overweight and lack of exercise increase the risk of hiatus hernia. You should therefore change your diet and lifestyle, i.e. exercise more often and eat smaller meals. It is also advisable not to eat anything right before going to bed. Particularly in the case of a known sliding hernia, a somewhat elevated upper body at night prevents abdominal organs from sliding up into the chest cavity again. It also means less heartburn and a lower risk of reflux disease and its consequences.

Because most hernias are harmless and painless sliding hernia, a diaphragmatic hernia usually proceeds without complications and its prognosis is good.