Lung cancer (bronchial carcinoma): warning signals, therapy

Lung cancer (bronchial carcinoma): warning signals, therapy

Lung cancer (bronchial carcinoma) is one of the most common cancers. The most important risk factor is smoking. Passive smoking can also lead to lung cancer. The malignant tumour can be treated in various ways, such as chemotherapy and surgery. Nevertheless, lung cancer is rarely curable. Read all the important information about lung cancer here!

Lung cancer: short overview

- Symptoms: initially often no or only unspecific complaints such as persistent coughing, chest pain and fatigue. Later on, symptoms such as shortness of breath, mild fever, severe weight loss and bloody sputum may occur.

- Main forms of lung cancer: The most common is non-small cell lung cancer (with adenoparcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, etc). Small cell bronchial carcinoma is rarer, but more aggressive.

- Causes: Especially smoking. Other risk factors include asbestos, arsenic compounds, radon, high levels of air pollution and a diet low in vitamins.

- Investigations: Chest X-ray (X-ray thorax), computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), examination of tissue samples (biopsies), positron emission tomography (usually in combination with CT as FDG-PET/CT), blood tests, examination of the sputum, examination of the “lung water” (pleural puncture)

- Therapy: Operation, radiotherapy, chemotherapy.

- Prognosis: Lung cancer is usually diagnosed late and is therefore rarely curable.

Lung cancer: Signs

Lung cancer (lung carcinoma) often causes no or only unspecific symptoms at first. These include fatigue, coughing or chest pain. Such complaints can also have many other causes, for example a cold or bronchitis. This is why lung cancer is often not detected in its early stages. This then makes therapy more difficult.

More pronounced signs cause lung cancer when it is already more advanced. Then, for example, rapid weight loss, bloody sputum and shortness of breath can occur.

If the lung cancer has already formed metastases in other regions of the body, further symptoms are usually added. For example, metastases in the brain can damage the nerves. Possible consequences are headaches, nausea, visual and balance problems or even paralysis. If the cancer cells have attacked the bones, arthrosis-like pain can occur.

You can read more about the various signs of lung cancer in the article Lung cancer: symptoms.

Lung cancer: stages

Like all cancers, lung cancer is caused by the degeneration of cells. In this case it is cells of the lung tissue. The degenerate cells proliferate uncontrollably and displace healthy tissue in their environment. Later, individual cancer cells can spread throughout the body via the blood and lymph vessels. Often they then form a metastasis elsewhere.

A lung cancer disease can therefore be at different stages of development. For example, one speaks of an early stage or – in the worst case – the final stage of lung cancer. But these are not precisely defined terms. Physicians therefore usually use the so-called TNM classification: it allows the individual stages of lung cancer to be described exactly. This is important because the treatment and life expectancy of a patient depends on the stage of lung cancer.

Lung cancer: TNM classification and stages

The TNM scheme is an international system to describe the spread of a tumour. It says:

- “T” for tumor size

- “N” for the possible infestation of lymph nodes (Nodi lymphatici)

- “M” for the possible presence of metastases

For each of these three categories a numerical value is assigned. It indicates how advanced the cancer of a patient is.

The exact TNM classification in lung cancer is complex. The following table should give a rough overview:

| TNM | Tumor character at diagnosis | Declaration |

| TX | Occult (hidden) carcinoma | Neither X-rays nor computed tomography (CT) can detect a tumour, but cancer cells can be found in the patient’s sputum. |

| T1 | The tumour is smaller than 3 cm. The main bronchus is not affected. | The main bronchi are the first branches of the trachea in the lungs. |

| T2 | The tumour has a size of 3 to 5 cm (T2a) or 5 to 7 cm (T2b) | and/or at least one of the following criteria is met:

|

| T3 | The tumour is larger than 7 cm | or at least one of the following criteria:

|

| T4 | The size of the tumour no longer plays a role here; instead, this stage is present when

|

|

| N0 | no lymph node infestation | |

| N1 | Ipsilateral lymph node involvement around the bronchial tubes (peribronchial) or at the point where the pulmonary vessels and main bronchi enter the lung (hilary) | The term “ipsilateral” means that the affected lymph node is located in the same half of the lung or body as the causative lung tumour. “Contralateral” means that lymph nodes of the other half of the body/lung are affected. |

| N2 | Ipsilateral lymph node involvement below the junction of the main bronchi (subcarinal) or the chest cavity between the two lungs (mediastinal) | |

| N2 | Ipsilateral lymph node infestation above the clavicle (supraclavicular) or on the neck or infestation of (at least) one contralateral lymph node | |

| M0 | No remote metastases | |

| M1a | Metastases in the contralateral lung and/or heavy infestation of the lung fur and/or cancer cells detectable in the effusion fluid of the lung fur | |

| M1b | Remote metastases | Liver, brain, bones and adrenal glands are usually affected by distant metastases |

The TNM classification determines the lung cancer stage: 4 stages are distinguished. The higher the stage, the more advanced the disease is:

Lung cancer stage I

This stage is divided into A and B. Stage IA corresponds to a classification of T1 N0 M0. This means that the malignant lung tumour is smaller than three centimetres. The main bronchus is not affected by cancer. In addition, no lymph nodes are affected and no distant metastases have yet formed.

In stage IB, the tumour has a classification of T2a N0 M0: it is three to five centimetres in size and is restricted to the lungs. The tumour has therefore neither affected lymph nodes nor spread to other organs or tissues.

In this first stage lung cancer has the best prognosis and is often still curable.

Lung cancer stage II

A and B are also distinguished here. Stage IIA includes lung tumours of category T2b that have not yet affected lymph nodes (N0) or formed metastases (M0). Tumours of the category T1 N1 M0 also fall in this subheading.

Stage IIB includes tumours of the classification T3 N0 M0 or T2b N1 M0.

Even in stage II lung cancer is still curable in some cases. However, the life expectancy of patients is already lower than in stage I.

Lung cancer stage III

Stage IIIA is present if the lung cancer is classified with T1/T2 N2 M0 or with T3 N1/2 M0 or with T4 N0 M0. Stage IIIB describes any lung cancer with N3 M0 or T4 N2 M0.

In lung cancer stage III, the tumour has already progressed to such an extent that patients can only be cured in rare cases.

Lung cancer stage IV

Life expectancy and chances of recovery are very low at this stage. The patient can only receive palliative therapy: It aims to relieve the symptoms and prolong survival time. Stage IV includes any lung cancer that has already formed distant metastases (M1). Tumour size and lymph node infestation then no longer play a role – they can vary.

Tumor size, lymph node involvement and metastasis are used to classify the stage of lung cancer

Small cell lung cancer: Alternative classification

Physicians distinguish two major groups of lung cancer: small cell lung cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (see below). Both can be divided into stages according to the TNM classification mentioned above.

For small cell lung cancer, another classification can be used alternatively:

- very limited disease: maximum to T2 and N1

- limited disease: T3/4 with N0/1 or T1 to T4 with N2/N3

- extensive disease: M1 independent of T and N

Lung cancer: treatment

The therapy of bronchial carcinoma is very complicated. It is individually adapted to each patient: Above all, it depends on the type and spread of lung cancer. However, the age and general health of the patient also play an important role in therapy planning.

If a treatment aims to cure lung cancer, it is called curative therapy. Patients in whom a cure is no longer possible receive palliative therapy. It is intended to maximally prolong the patient’s life and alleviate their complaints.

Doctors from different departments of a hospital consult with each other about the final treatment strategy. These include radiologists, surgeons, internists, radiologists and pathologists. In regular sessions (“tumour boards”) they try to find the best lung cancer therapy for a patient.

There are three different therapeutic approaches, which are used individually or in combination:

- surgery to remove the tumor

- chemotherapy with special drugs against the cancer cells

- the irradiation of the tumour

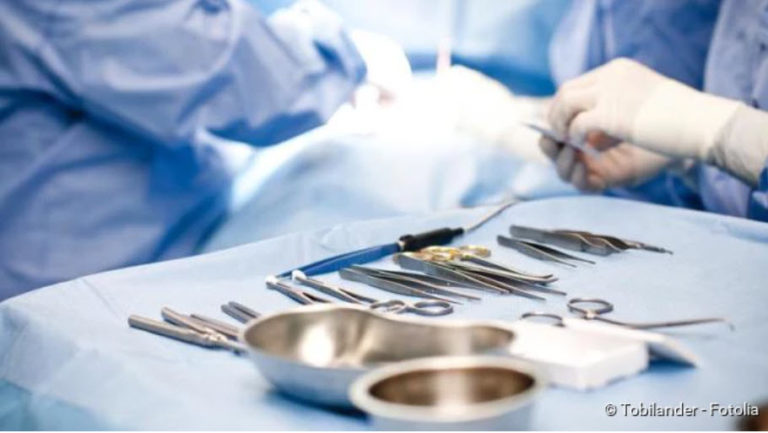

Lung cancer: surgery

A real chance of recovery from lung cancer usually exists only as long as it can be operated on. The surgeon attempts to remove all of the lung tissue affected by the cancer. It also cuts a rim out of healthy tissue. In this way he wants to make sure that no cancer cells are left behind. Depending on the spread of the bronchial carcinoma, either one or two lobes of the lung are removed (lobectomy, bilobectomy) or even an entire lung (pneumonectomy).

In some cases it would be useful to remove an entire lung. However, the poor state of health of the patient does not allow this. Then the surgeon removes as much as necessary, but as little as possible.

During the operation the surrounding lymph nodes are also cut out (mediastinal lymph node dissection). This is done even if the preliminary examinations have not given any indication of cancer of the lymph nodes. Often these are the first stop for a resettlement, which is not obvious at the beginning.

Unfortunately, there is often no longer a chance that an operation can cure lung cancer: The tumor is already too far advanced. In other patients, the tumour would in principle be operable. However, the patient’s lung function is so poor that he would not be able to cope with removing parts of the lung. In the run-up to the operation, the doctors therefore carry out special examinations to determine whether an operation is advisable for a patient.

Lung cancer: chemotherapy

Lung cancer, like many other types of cancer, can be treated with chemotherapy. The patient receives drugs that inhibit cell division and thus tumor growth. These active substances are called chemotherapeutic or cytostatic drugs.

Chemotherapy alone is not enough to cure lung cancer. They are therefore usually used in combination with other treatments. It can, for example, be carried out in the run-up to an operation to reduce the size of the tumour (neoadjuvant chemotherapy). Then the surgeon must cut out less tissue.

In other cases, chemotherapy is performed after the operation: It is designed to destroy cancer cells that may still be present in the body (adjuvant chemotherapy).

Chemotherapy for lung cancer usually consists of several treatment cycles. So there are certain days on which the doctor administers the medication. In between there are two to three weeks of treatment breaks. The patient usually receives the active ingredients as an infusion through a vein. However, sometimes the preparations are also given in tablet form (orally).

To check the effect of chemotherapy, the patient is regularly examined by means of computer tomography (CT). In this way the doctor can see whether he has to adjust the chemotherapy. For example, he can increase the drug dose or prescribe another cytostatic drug.

Lung cancer: Irradiation

Another approach to lung cancer treatment is irradiation. Lung cancer patients usually receive radiotherapy in addition to another form of treatment. Similar to chemotherapy, radiation can be administered before or after an operation, for example. They are often used in addition to chemotherapy. This is called radiochemotherapy.

Some lung cancer patients also receive so-called prophylactic cranial radiation. This means that the skull is irradiated as a precaution to prevent the development of brain metastases.

If the lung cancer is still in a very early stage, radiation alone is sometimes sufficient to cure the patient.

Other treatments for lung cancer

The above-mentioned therapies directly target the primary tumour and possible lung cancer metastases. In the course of the disease, however, various complaints and complications can occur, which must also be treated:

- If an effusion forms between the lung and the lung membrane (pleural effusion), it is aspirated (pleural puncture). If the effusion reoccurs, a small tube can be inserted between the pleura and the pleura to drain the fluid. It remains longer in the body (thoracic drainage).

- The tumor can cause bleeding in the bronchial tubes. These can be stopped, for example, by specifically closing the blood vessel in question, for example during a bronchoscopy.

- The growing tumour can block blood vessels or airways. To make them continuous again, a stent can be inserted, i.e. a stabilizing tube. In other cases, the tumor tissue is removed at the site in question, for example with a laser.

- Advanced lung cancer can cause severe pain (tumor pain). The patient then receives a suitable pain therapy, for example painkillers in the form of tablets or injections. In the case of painful bone metastases, irradiation can provide relief.

- Respiratory distress can be alleviated with medication and oxygen. Special breathing techniques and the correct positioning of the patient are also helpful.

- In case of severe weight loss, the patient may need to be fed artificially.

- Side effects of chemotherapy such as nausea and anaemia can be treated with suitable drugs.

In addition to the treatment of the physical complaints, it is also very important that the patient receives good mental care. Psychologists, social services and self-help groups help with the processing of the illness. This improves the patient’s quality of life. The relatives can and should also be included in the therapy concepts.

In its early stages, lung cancer is often asymptomatic or non-specific. For example, you may experience a persistent cough or you may feel exhausted. Later complications such as pneumonia can occur – but by then lung cancer is usually already in an advanced stage.

Lung cancer is an aggressive disease that very often leads to death. This process can only be stopped if you as a patient put diagnostics and therapy first. This means: Avoid delays caused by weekend activities, holidays or stays in rehabilitation clinics, for example. This can have fatal consequences. Concentrate fully on your treatment.

The therapy of lung cancer has made significant progress in recent years. Modern, molecular methods enable “targeted therapies” – i.e. a targeted cancer therapy that is directed as far as possible only against the cancer cells and is therefore better tolerated and more effective. Visit a practice or clinic that uses these modern methods in diagnostics and therapy.

Small cell bronchial carcinoma

The treatment of lung cancer is influenced by the type of tumour. Depending on which cells of the lung tissue become cancer cells, physicians differentiate between two large groups of lung cancer: One of these is small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

This form of lung cancer grows very quickly and forms metastases in other parts of the body at an early stage. Therefore, chemotherapy is the most important therapeutic method here. Many patients also receive radiation therapy. This should improve the chances of success of the treatment.

Surgery usually only makes sense if the tumour is still very small and no or only a few neighbouring lymph nodes are affected. But this only applies to individual patients: At the time of diagnosis, small cell lung cancer is usually already more advanced.

You can read more about the development, treatment and prognosis of this form of lung cancer in the article SCLC: Small Cell Lung Cancer.

Non-small cell lung cancer

Non-small cell lung cancer is the most common form of lung cancer. It is often abbreviated with NSCLC (“non small cell lung cancer”). Strictly speaking, the term “non-small cell lung cancer” covers various types of tumours. These include adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

The following applies to all non-small-cell bronchial carcinomas: They grow more slowly than small-cell lung cancer and only form metastases later. They do not respond well to chemotherapy for this.

The treatment of choice is therefore surgery, if possible: In this procedure, the surgeon attempts to remove the tumor completely. If this is not possible, the patient receives additional radiation. Before or after the operation, chemotherapy can also be used as a support. If non-small cell lung cancer is discovered at a very early stage, radiation alone may be sufficient under certain circumstances.

For some time now, there have been other therapeutic approaches such as treatment with antibodies. They are only suitable for certain patients.

You can read more about this widespread form of lung cancer in the article NSCLC: Non-small cell lung cancer.

Lung cancer: causes and risk factors

The reason for lung cancer is an uncontrolled growth of cells in the so-called bronchial system. These are the large and small airways of the lungs (bronchi and bronchioles). The medical term for lung cancer is therefore bronchial carcinoma. The word part “carcinoma” stands for a malignant tumour consisting of so-called epithelial cells. They form the covering tissue that lines the airways.

The uncontrolled growing cells multiply very quickly. Debei they are increasingly displacing healthy lung tissue. In addition, the cancer cells can spread via the blood and lymphatic system and form a daughter tumour elsewhere. Such metastases are called lung cancer metastases.

Lung cancer metastases should not be confused with lung metastases: These are daughter tumours in the lungs that originate from cancer tumours elsewhere in the body. For example, colon cancer and renal cell cancer often cause lung metastases.

Smoking: The main risk factor

The most important risk factor for uncontrolled and malignant cell growth in the lungs is smoking. About 90 percent of all men with lung cancer have smoked actively or are still doing so. In women, this applies to at least 60 percent of patients. The earlier someone starts smoking and the more one smokes, the higher the risk of disease.

Physicians measure the previous cigarette consumption of a patient in the unit “pack years”. If someone smokes a pack of cigarettes a day for a year, this is counted as “one pack year”. If he smokes one pack a day for ten years or two packs a day for 5 years, that is 10 pack years each. The following applies: the more years of packages, the higher the risk of lung cancer.

Besides the number of cigarettes smoked, the type of smoking also plays a role: the more smoke you inhale, the worse it is for your lungs. The type of cigarette also has an influence on the risk of lung cancer: strong or even filterless cigarettes are particularly harmful.

It has also been known for some years that adolescents and women are more sensitive to the carcinogenic substances in tobacco smoke than adults and men.

However, not everyone who has smoked for a few years in their past has to be afraid of lung cancer. Because fortunately the lungs can recover. Only a few years after stopping smoking, the risk of lung cancer has already decreased noticeably. About 20 to 30 years after the last cigarette, an ex-smoker again has about the same risk of disease as someone who has never smoked. So it’s never too late to quit smoking.

Passive smoking also increases the risk of lung cancer!

Other risk factors for lung cancer

Apart from smoking, there are other factors that can increase the risk of lung cancer:

- Materials such as asbestos, arsenic compounds or quartz and nickel dusts

- high pollution of the air: the most important factor is diesel soot. Particulate matter also appears to have a negative influence on the risk of lung cancer.

- Radon: The natural, radioactive gas is concentrated in certain areas. It is found there mainly in the lower floors of buildings.

- Genes: To a certain extent, lung cancer seems to be inheritable. Experts suspect a genetic predisposition, especially in very young patients. This could make them more susceptible to lung damage (such as smoking).

- Lung scars: They occur, for example, as a result of tuberculosis or after operations.

- Viruses: Viral diseases can also be involved in the development of bronchial cancer. HIV and human papilloma viruses (HPV) are suspected.

- Low vitamin diet: Eating little fruit and vegetables apparently increases the risk of lung cancer. This is especially true for smokers. However, taking vitamin preparations is not an alternative: especially for smokers, such preparations seem to increase the risk of bronchial cancer even further.

If several of these factors are present at the same time, the probabilities of lung cancer do not only add up: in fact, the risk of developing the disease increases many times over. For example, high levels of air pollution increase the risk of lung cancer much more in smokers than in non-smokers.

Sometimes no cause for lung cancer can be found. One then speaks of an idiopathic illness. Of all types of lung cancer, the most common is the so-called adenocarcinoma. This is a form of non-small cell lung cancer.

Lung cancer: examinations and diagnosis

The diagnosis of lung cancer is often made late. Symptoms such as persistent coughing, chest pain and shortness of breath are often not recognized as possible signs of lung cancer, especially by smokers. Usually the patients simply blame the smoking. Others suspect a severe cold, bronchitis or pneumonia behind the symptoms. Only medical examinations then reveal a suspicion of bronchial carcinoma.

The first point of contact for possible symptoms of lung cancer is the family doctor. If necessary, he will refer the patient to specialists, for example to an X-ray specialist (radiologist), lung specialist (pneumologist) or cancer specialist (oncologist). In order to be able to make a diagnosis of lung cancer, a medical history, a physical examination and various instrumental examinations are necessary.

Medical history and physical examination

First of all, the physician creates the patient’s medical history (anamnesis) in consultation with the patient:

He can have a precise description of the symptoms that occur, such as shortness of breath or chest pain. He also asks about risk factors for lung cancer: For example, he asks whether the patient smokes or is professionally involved with materials such as asbestos or arsenic compounds.

Important for the diagnosis of lung cancer is also information on possible pre-existing or underlying diseases such as COPD or chronic bronchitis. Patients should also tell the doctor if there have been cases of lung cancer in their family.

After the medical history interview, the doctor will carefully examine the patient physically. For example, it taps and listens to the patient’s lungs and measures blood pressure and pulse. The examination can provide possible clues as to the cause of the complaints. It also enables the doctor to better assess the patient’s general state of health.

X-ray

By means of an X-ray of the chest (X-ray thorax) the doctor can already detect certain changes in the lung tissue. If this results in the suspicion of lung cancer, the next step is computer tomography (CT).

By the way: The doctor x-rays the patient in two planes, i.e. from the front and from the side.

Computer tomography (CT)

Computer tomography provides detailed sectional images of the lungs in high resolution. This is possible with the help of X-rays that are much more highly dosed than a normal X-ray. In addition, the patient is given a contrast medium in advance. In this way, the different tissue structures can be better represented.

With the help of CT, the doctor can assess suspicious lung changes better than with x-rays. This may confirm the suspicion of lung cancer.

Examination of tissue samples (biopsy)

To be sure whether a conspicuous spot in the lung tissue is actually a bronchial carcinoma, a small piece of tissue must be removed and examined under the microscope. Depending on the location of the suspicious area, different methods are used:

In lung endoscopy (bronchoscopy), a tube with a tiny camera (endoscope) is inserted via the mouth or nose into the patient’s trachea and further into the bronchial tubes. When looking inside, a tumour can often be recognised visually. In addition, the doctor can take tissue samples and secretions from the lungs during bronchoscopy with fine instruments under visual control.

If it is difficult or impossible to reach the suspicious tissue via the bronchial tubes, the doctor performs a so-called transthoracic needle aspiration: In doing so, he pricks between the ribs from the outside with a very fine needle. Under CT control, he guides the needle tip to the suspected lung area. Via the needle it then sucks (aspirates) some tissue.

In some patients neither bronchoscopy nor transthoracic needle aspiration is possible. In other cases, both investigations do not provide a clear result. A surgical biopsy may then be necessary: Either the surgeon opens the chest with a larger incision (thoracotomy) and takes a sample of the suspicious tissue. Or he makes small incisions in the chest through which he introduces a small camera and fine instruments for tissue sampling (Video Assisted Thoracoscopy, VATS).

The tissue sample taken is examined under the microscope. As a rule, it is possible to determine whether lung cancer is present and, if so, what type of tumour it is (cytological diagnosis). Only in special cases is it necessary to examine larger tissue sections (histological diagnosis).

Investigation of tumor spread (staging)

Once a diagnosis of “lung cancer” has been made, the next step is to examine how it is spreading in the body. Doctors call this part of the examination “staging”. Only through such staging can they classify the bronchial carcinoma according to the TNM classification.

Staging comprises three steps:

- Examination of tumor size (T-status)

- Examination of the lymph node involvement (N status)

- Search for metastases (M status)

Examination of the primary tumour (T-status)

First, the size of the tumour from which the lung cancer originates (primary tumour) is examined. For this purpose, the patient is given a contrast medium before his chest and upper abdomen are examined by means of computer tomography (CT). The contrast agent accumulates for a short time, especially in the tumor tissue, and causes a marker to appear on the CT image. This enables the physician to assess the extent of the primary tumor.

If the CT examination is not conclusive enough, other procedures are used. This can be, for example, an ultrasound examination of the chest (thoracic sonography) or a magnetic resonance tomography (MRT).

Examination of the lymph node involvement (N status)

In order to be able to plan the therapy optimally, the doctor must know whether the lung cancer has already affected lymph nodes. Here, too, the examination by means of computer tomography (CT) is helpful. A special technique is often used for this: the so-called FDG-PET/CT. This is a combination of positron emission tomography (PET) and CT:

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a nuclear medical examination. First, a tiny amount of a radioactive substance is injected into a vein of the lying patient. The FDG-PET/CT is FDG. This is a radioactively labelled simple sugar (fluorodeoxyglucose). It is distributed throughout the body and accumulates particularly in tissues with increased metabolic activity, such as cancer tissue. During this time, the patient must lie as still as possible. After about 45 (to 90) minutes, the PET/CT scan is performed to visualize the distribution of FDG in the body:

The PET camera can very well map the different metabolic activity in the different tissues. Particularly active areas (such as cancer cells in lymph nodes or metastases) literally “light up” on the PET image. Bones, organs and other structures of the body, however, cannot be represented so well by PET. This is done almost simultaneously by computer tomography, CT (PET camera and CT are combined in one device). It allows a very precise representation of the various anatomical structures. In combination with the exact mapping of metabolic activity, cancer foci can be precisely localized.

Conclusion: Using FDG-PET/CT, metastases of lung cancer in lymph nodes and also more distant organs and tissues can be visualized very accurately. To be on the safe side, the doctor may take a tissue sample from the suspicious areas and examine it for cancer cells (biopsy).

Search for metastases (M status)

The scattering of cancer cells into other organs is a major problem in bronchial carcinoma. Metastases form particularly often in the liver and brain as well as in the bones and adrenal glands. In principle, however, any body structure can be attacked by the cancer cells. Lung cancer that has already spread is considered to be incurable.

With the special examination FDG-PET/CT described above, metastases can be detected everywhere in the body. In order to detect possible metastases in the brain, the skull is also examined by means of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

In some patients FDG-PET/CT is not possible. The alternative is then a computer tomography or ultrasound examination of the trunk and additionally a so-called bone scintigraphy. Whole body MRI images are also possible.

Blood tests

There are no blood tests that can be used to diagnose lung cancer with certainty. However, so-called tumour markers can be determined in the blood. These are substances whose blood levels can be elevated in the case of a crescent disease. This is because the tumour markers are either produced by the cancer cells themselves or by the body in response to the cancer.

Physicians are aware of two tumor markers that are often elevated in lung cancer: neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and CYFRA 21-1, but these markers alone are not sufficient to make a diagnosis. Rather, they serve to assess the course of the disease: Their concentration in the blood is determined regularly. This enables the doctor to estimate how fast the tumour is growing or whether cancer cells will reappear after treatment.

Examination of the sputum

The sputum that a patient coughs up from the lungs can also be examined. This method is mainly used when other diagnostic procedures are not possible (e.g. because the patient’s state of health is too poor).

If the sputum is inconspicuous, this does not necessarily mean that there is no lung cancer. The examination of the sputum is more likely to confirm an already existing suspicion.

Examination of lung water

In lung cancer patients, “lung water” often forms. This means that more and more fluid collects between the pleura and the pleura. However, such a pleural effusion can also have other causes. For clarification, the doctor will take a sample of the effusion using a fine hollow needle (pleural puncture) and examine it microscopically. In this way he can determine what caused the effusion.

Are there screening tests for lung cancer?

A general early detection, as used for example for breast cancer, colon cancer or skin cancer, is difficult in the case of lung cancer. For example, one could regularly take X-rays of the chest, examine the blood for tumour markers or analyse the sputum. However, such preventive examinations are either too inaccurate or too sensitive. In the second case, unfounded suspicion of cancer could arise. In addition, regular X-ray or CT examinations mean that the person concerned is exposed to radiation.

However, people who are at high risk of lung cancer could benefit from screening. For example, studies have been carried out in which high-risk patients have been regularly examined using computed tomography (CT) with low radiation doses. In this way, for example, bronchial cancer could be detected earlier in heavy smokers. However, this needs to be further investigated. Only then can one perhaps recommend such preventive examinations for certain risk groups.

Lung cancer: course of disease and prognosis

There is a special aftercare plan for patients who have received therapy with the intention of healing (curative therapy). After completion of the treatment, they should go to the hospital at regular intervals for check-ups. Regular X-ray and CT images are particularly important. The physician will evaluate each of these in comparison to the last images of the patient.

Patients who are no longer expected to be cured are also regularly examined by a doctor. In this way it can be determined whether palliative therapy sufficiently alleviates the symptoms or whether it may be necessary to adjust the therapy.

Lung cancer: prognosis

Overall, bronchial carcinoma has a poor prognosis: lung cancer is often only discovered in many patients when the disease is already well advanced. A cure is then often no longer possible. If the lung cancer is discovered in the early stages, surgery may be possible. After some time, however, a new cancer tumor often develops (relapse = recurrence).

Precisely because the chances of recovery are so low, it is important not to increase the risk of lung cancer unnecessarily. The most important factor that everyone has in their own hands is smoking. Those who refrain from smoking or do not start smoking in the first place significantly reduce their personal risk of bronchial carcinoma. The prognosis and course of existing lung cancer can also be improved by stopping smoking.

Lung cancer: life expectancy

People who are diagnosed with lung cancer often ask themselves, “How long will I live?” It is not easy for the doctor to answer this question. After all, life expectancy in lung cancer depends on various factors:

For example, it plays a role in how far advanced the tumour is at the time of diagnosis. Lung cancer is often discovered late, which has a negative impact on the patient’s life expectancy. The type of tumour also has an influence on survival: non-small cell lung cancer grows more slowly than small cell lung cancer. They therefore generally have a better forecast.

The general state of health is also important: if, for example, the heart and lung function of a patient is significantly weakened, it may be that certain forms of treatment can only be carried out to a limited extent or not at all. This can significantly reduce the life expectancy of lung cancer patients.

For more information on life expectancy and chances of recovery from lung cancer, see the text Lung cancer: life expectancy.