Lymphoma – Lymph gland cancer: forms, signs, treatment

Lymphoma – Lymph gland cancer: forms, signs, treatment

Lymph gland cancer (malignant lymphoma) is a malignant disease of the lymphatic system. Typical symptoms are painlessly swollen lymph nodes, as well as fever, weight loss and night sweats. Lymph gland cancer can occur at any age. Men are affected by lymph gland cancer slightly more frequently than women. Therapy and prognosis depend on the lymph node cancer type and the lymph node cancer stage. Physicians differentiate between Hodgkin’s lymphoma and so-called non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Here you can read everything important about malignant lymphoma (lymph gland cancer).

Lymphoma (lymph gland cancer): Description

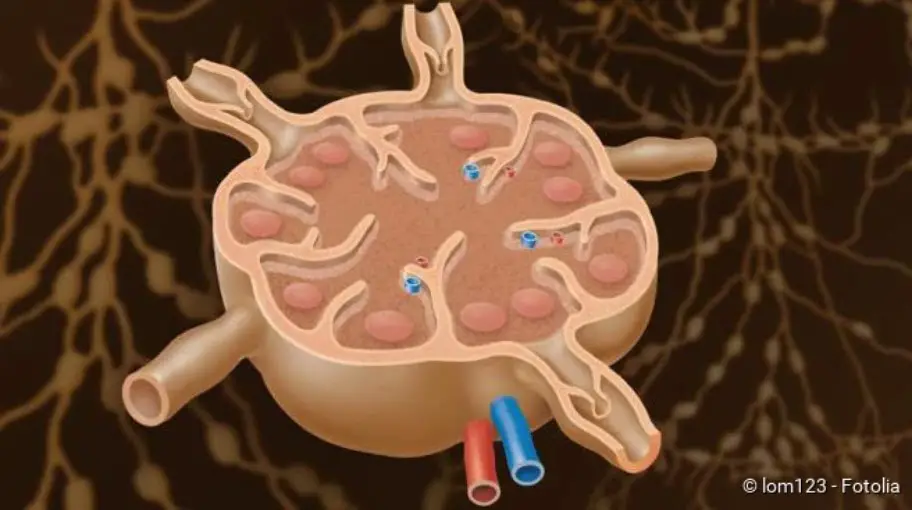

Lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) (formerly also known as lymphosarcoma) affects the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system is an important part of the body’s own defence system. It consists of the lymphatic organs like spleen and bone marrow and the lymph vessels with intermediate lymph nodes. The lymphatic system serves to mature and imprint a certain type of white blood cells, the lymphocytes (= lymph cells). There are two important types of lymph cells that have different tasks. The T-lymphocytes recognize and mark foreign substances such as viruses and bacteria so that they can be subsequently destroyed. The B-lymphocytes produce antibodies that serve to fight pathogens and foreign bodies.

The lymph nodes filter the tissue fluid (lymph) and are an important component of the immune system. The spleen is also an important immunological organ and also breaks down old or defective red blood cells (erythrocytes).

A malignant lymphoma is particularly noticeable in the lymph nodes and the spleen. Lymph gland cancer can, however, also spread beyond the lymphatic system and in the course of time can affect other organs.

Lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) develops when a lymph cell degenerates and becomes a cancer cell. This can be either the tissue of the spleen, the lymph nodes or degenerated white blood cells such as B-lymphocytes or degenerated T-lymphocytes. The cells differ in appearance and function from healthy lymph cells and are no longer able to repair themselves. As a result, the defective lymph cells multiply and displace healthy cells of the blood formation. Since the lymphocytes can no longer fulfil their normal functions, lymphoma can lead to a weakness of the immune system, especially due to a lack of functional antibodies (antibody deficiency syndrome).

In general, men are more frequently affected by lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) than women. About two thirds of the patients are male. The age of the disease depends on the type of lymphoma (lymph gland cancer). There are forms that occur primarily in people over the age of 50. Other forms, such as Hodgkin’s lymphoma or certain non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, can also affect children and young people. Unfortunately, lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) in childhood is not uncommon. Malignant lymphomas are the third most common type of cancer among childhood and adolescent tumors, accounting for twelve percent of all cancers.

Many different types of lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) are distinguished. There are two major groups to which the diseases are assigned. The so-called “Hodgkin lymphoma” (Hodgkin’s disease) and the “Non Hodgkin lymphomas“.

Lymphoma (lymph gland cancer): Hodgkin’s disease

Hodgkin’s disease often affects young people. You will find detailed information about this disease in the article Hodgkin’s disease.

Lymph gland cancer: non-Hodgkin lymphomas

About 85 percent of all cases of lymph gland cancer are non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Read all about this in the article Non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

Lymphoma – Lymph gland cancer: Symptoms

You can read everything important about the typical signs of lymph node cancer in the article Lymph node cancer symptoms.

Lymphoma (lymph gland cancer): Causes and risk factors

The exact causes of lymph gland cancer are not yet known. However, physicians have identified various lymph node cancer risk factors. In the individual case of illness, however, it usually remains completely unclear how the lymphoma developed. In addition, the risk factors differ for the various forms of lymphoma (lymph gland cancer).

Chemical substances, radiation exposure or viruses can contribute to the degeneration of cells and prevent them from repairing themselves. The degenerated lymph cells then collect in a lymph node or other lymphatic organ, which swell due to the increased cell division. Doctors assume the following risk factors for the various forms of lymphoma (lymph gland cancer).

Risk factors for Hodgkin’s lymphoma:

This form of lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) is promoted by an infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). The Epstein-Barr virus is mainly responsible for the so-called Pfeiffer’s glandular fever (infectious mononucleosis). According to scientific studies, a past infection seems to significantly increase the risk of Hodgkin lymphoma. In 50 percent of patients, the EB virus can be detected in the lymphoma cells.

It is also currently being discussed whether HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) infection increases the risk of Hodgkin lymphoma. This seems likely because people with HIV infection have a significantly increased risk of cancer due to the weakened immune system. Chemotherapy or the intake of drugs that are supposed to weaken the immune system (immunosuppressants) also promotes the development of Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Risk factors for non-Hodgkin lymphomas

In the development of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, similar factors play a role in as in Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Infection with the Eppstein-Barr virus is also considered a risk factor for this form of lymph gland cancer. In addition, an inflammation of the gastric mucosa, caused by the bacterium “Helicobacter pylori”, seems to be favourable for a lymphoma of the gastric mucosa (MALT=Mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma).

People with HIV infection have a thousandfold increased risk of developing non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Harmful substances such as aromatic hydrocarbons (such as benzene), chemotherapy, radiation or prolonged suppression of the immune system by drugs (immunosuppressants) also increase the risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Lymphoma (lymph gland cancer): examinations and diagnosis

The right person to contact if lymph gland cancer is suspected is your family doctor or a specialist in internal medicine and oncology. Swollen and painless lymph nodes can have different causes – so it does not necessarily have to be lymph node cancer. However, if the painless swelling of the lymph nodes persists for weeks and symptoms such as fever, night sweats and unwanted weight loss also occur, you should urgently consult a doctor for clarification. He will conduct a detailed interview (anamnesis) on the complaints. Possible questions from your doctor may be included:

- Have you lost weight unintentionally in the last few months? (More than 10 percent of the initial weight in the last six months is conspicuous)

- Have you woken up at night recently because you were “bathed in sweat”?

- Have you had a frequent fever and felt weak in the past?

- Have you noticed any painlessly enlarged lymph nodes (for example on the neck, under the armpits or in the groin)?

- Do the swollen lymph nodes hurt after alcohol consumption (indicating Hodgkin’s lymphoma)?

Physical examination

During the physical examination, the enlarged lymph nodes can be palpated. If they are enlarged due to the disease, the enlarged spleen under the left costal arch or an enlarged liver under the right costal arch can also be palpated.

Further investigations

Blood test and immunohistochemistry

A decisive diagnostic tool in lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) is blood testing. In a lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) blood count, changed numbers of blood cells can be recorded. Due to the strong proliferation of the degenerated lymphoma cells, the other cells of the blood are displaced, so that anemia, a lack of blood platelets (thrombocytopenia) and of functioning defence cells (leukopenia) can be conspicuous in the lymph gland cancer blood count. Typical for Hodgkin’s disease is an increase in the number of so-called eosinophilic granulocytes (eosinophilia).

The function of the kidney and liver can also be determined in the blood count. This shows how much lymph gland cancer has already affected other organs. In addition, elevated inflammation values can be observed in the blood, which manifest themselves mainly through increased blood sedimentation.

The blood can also be examined immunohistochemically. This means that the blood cells are analysed for certain characteristics on their cell surface. Among other things, antibodies and certain chemical substances are used to identify these surface characteristics (hence “immunohistochemistry”). With the immunohistochemical examination of non-Hodgkin lymphomas it can be distinguished whether degenerated B- or T-lymphocytes were the origin of the lymphoma. B-lymphocytes carry the surface feature “CD20”, T-lymphocytes “CD3” on their surface.

Tissue sample (biopsy)

On the basis of a tissue sample (biopsy) it can be determined with certainty what type of lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) it is. Usually, the surgeon takes a complete lymph node extirpation (lymph node extirpation), which he examines under the microscope. If the suspicion of a malignant lymphoma is confirmed, further imaging procedures are necessary.

The taking of a tissue sample is necessary for diagnosis. A reliable diagnosis of lymph gland cancer can only be made with a precise evaluation of the cells under the microscope. Besides the examination of lymph nodes, biopsies can also be taken from other tissues. For example, if skin lymphoma is suspected, a sample is taken from the skin; if MALT lymphoma is suspected, a sample is taken from the stomach lining.

Imaging methods

An X-ray, ultrasound or computer tomography (CT) helps to classify lymph node cancer and its stage. In some patients an additional examination of the bone marrow is necessary. The iliac crest is usually punctured with a needle under light sedation and some bone marrow is aspirated. The bone marrow is then examined under the microscope.

Staging (according to Ann-Arbor)

Lymph gland cancer (malignant lymphoma) is classified into one of four stages of the so-called Ann-Arbors classification (“staging“) on the basis of the examination results. This classification was originally developed for Hodgkin’s lymphoma, but is now also commonly used for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. In the classification, lymphoma is assigned to one of the four stages based on the extent to which it spreads in the body. The exact classification of the stages is very important, as the therapy plan is also based on this and an assessment can be made regarding the prognosis.

Lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) – stage classification according to Ann-Arbor

| Stadium | Infestation of the lymph nodes |

| I | Infestation of only one lymph node region |

| II | Only on one side of the diaphragm: (lymph nodes either in the thorax or abdomen): infestation of two or more lymph node regions |

| III | On both sides of the diaphragm: (lymph nodes both in the thorax and abdomen): Infestation of two or more lymph node regions |

| IV | Infestation of one or more extralymphatic organs (brain, bones) regardless of the pattern of lymph node infestation. |

Lymphoma (lymph gland cancer): treatment

A malignant lymphoma should always be treated in a specialized clinic. These are usually haematological-oncological or internal medicine wards of a university hospital. Depending on the stage of the disease, an individual therapy plan is drawn up. Therapy options include chemotherapy and/or radiation. Antibody therapy is also used to treat some malignant lymphomas. Patients with slowly progressing lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) who are free of symptoms can occasionally be spared treatment if the prospect of complete recovery is low. However, lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) must be closely monitored (“watch and wait”).

Chemo- and radiotherapy for lymphoma (lymph gland cancer):

Chemo- and radiotherapy is specifically directed against the cancer cells. Healthy cells and cancer cells are damaged equally. But since cancer cells have lost their ability to repair themselves, they die.

Lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) is divided into malignant (high malignancy) and less malignant (low malignancy) on the basis of growth pattern. Paradoxically, high malignant lymphomas do not have a worse prognosis than low malignant ones. Although the highly malignant lymphomas grow much faster, radiation and chemotherapy are much more effective due to the high cell division rate. On the other hand, the slow cell division in the cancer cells of low malignant lymphomas means that the therapy is not as effective.

In the early stages of lymphoma (lymph gland cancer), radiation therapy is the main treatment option due to the still limited spread of the disease in the body. The “involved-field technique” is applied. This means that, if possible, only the affected cancer areas are irradiated and the neighbouring healthy regions are excluded from the irradiation.

In Hodgkin’s disease, chemotherapy is used in addition to radiotherapy at an early stage. Since chemotherapy involves cytotoxins, some patients suffer from side effects such as diarrhoea, nausea and hair loss. How well the therapy is tolerated depends on the lymph node cancer stage and the general condition of the patient.

Detailed information on the treatment of the different types of lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) can be found in the articles Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas.

Further treatment options for lymphoma (lymph gland cancer):

Antibody therapy is relatively new. The cancer cells have certain proteins on their surface (surface characteristics). The administered antibodies can recognize these proteins and form a complex with the defective cell, whereupon the cell is destroyed. For example, the antibody rituximab against the surface feature “CD20” is used to treat B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas.

Many lymph node cancer patients also benefit from a bone marrow transplant. The stem cells can usually be obtained from the patient’s blood. This is followed by high-dose chemotherapy to completely kill the haematopoietic cells (including cancer cells). Immediately afterwards, the previously removed stem cells from the blood are implanted into the patient. The aim is to restore normal blood formation without cancer cells.

Lymphoma (lymph gland cancer): course of disease and prognosis

Whether lymph node cancer is curable depends on the stage and histological form of the disease. For example, Hodgkin’s disease is treated with a curative approach at every stage. This means that at every stage there is a chance for healing. On the other hand, in the case of an advanced, low-malignant non-Hodgkin lymphoma, for example, a cure is no longer possible in many cases. Accordingly, the lymph gland cancer life expectancy and the lymph gland cancer cure chances cannot be determined in a generalized way. How well the patient responds to the therapy depends on the type and stage of the disease, as well as any complications.

Lymph gland cancer (malignant lymphoma) progresses very slowly in some patients, especially the low malignant forms. Thus, lymph gland cancer in early stages of the disease occasionally causes no or only very minor symptoms. However, the earlier lymph gland cancer is discovered, the better the prognosis in general and the more “gentle” the therapy. Fortunately, malignant lymphoma is often discovered early, so that a cure is possible in many cases. However, there is a further limitation that radiation and chemotherapy can lead to new cancers after years or decades as a result of lymphoma (lymph gland cancer) therapy.